Short Stories & Long One-Liners

Irish green and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Photo by Marla Norman.

by Marla Norman, Publisher

It’s true! Flying into Dublin, I catch a glimpse of the countryside — flashes of green — so color-rich it shocks the senses while simultaneously soothing them in minty cadmium lushness. Yes! Ireland is extraordinarily green.

Rushing through showers for an airport cab, I confirm another Irish truism: The island is green because it rains frequently. Maybe even a bit more than frequently. I don’t care. I came prepared. Unpacking boots and umbrellas, I head out to meet “Dublin’s fair city.”

The Campanille, or bell tower, is an enduring symbol of Trinity College. Photo by Marla Norman

Trinity College is my first destination. The Old Library with its treasure of illuminated manuscripts seems like the perfect place to spend a rainy afternoon. But somewhere along the way I get turned around. I try to read a soggy map while holding onto a dripping umbrella. Suddenly, a booming voice yells out, “ARE YOU ALRIGHT?”

I’m taken-aback at first, but the loud voice belongs to a dapper businessman in a neat Burberry raincoat. And he’s ready to assist. He escorts me all the way to the campus, while telling stories about his undergraduate years at Trinity in a rich Irish brogue.

I’m grateful and surprised by the generous gesture. Yet, throughout Ireland, I had similar experiences. Anytime I got lost, inevitably, a local would come to the resuce, typically yelling “ARE YOU ALRIGHT” first. Then enthralling me with witty stories and anecdotes.

So, I discover a third axiom: No nationality is more charming than the Irish. And a huge part of that charm are the stories: happy, strange, heart-breaking, and belly-laugh-inducing. George Bernard Shaw got it right: “An Irishman’s heart is nothing but his imagination.”

THE OLD LIBRARY & BOOK OF KELLS

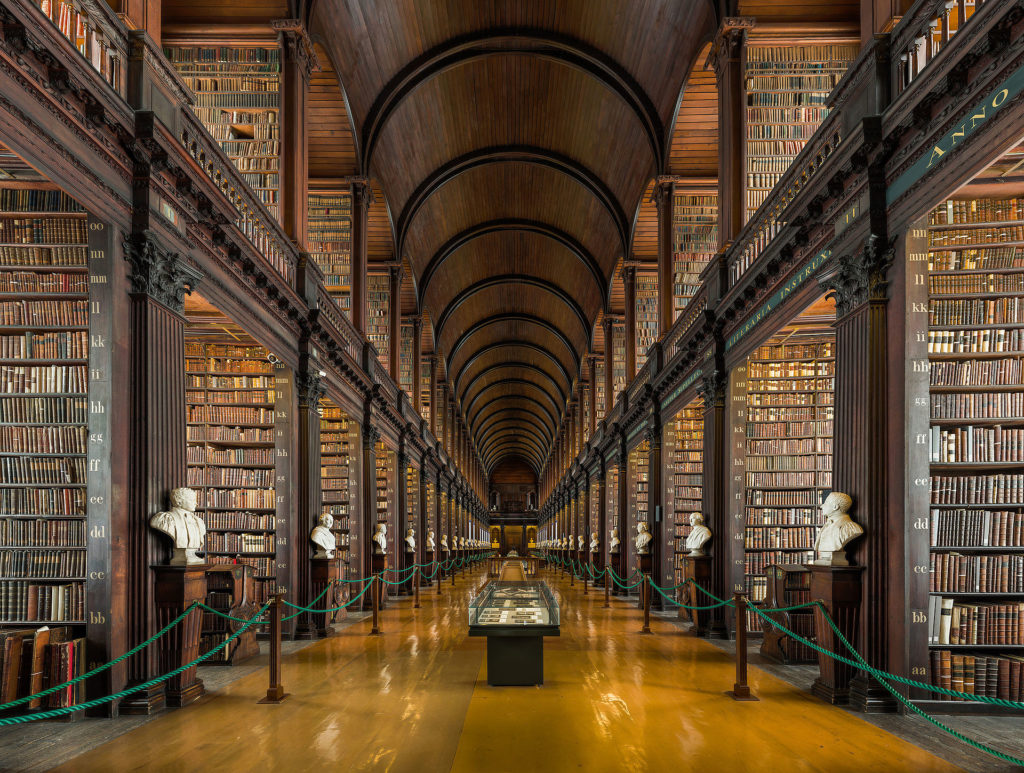

The Long Room, at Trinity College Library, is every book lovers’ fantasy. Huge, thick, ancient volumes fill 21 alcoves that rise two stories high to a barrel-vault ceiling. A total of three million titles are catalogued in the library. Of all the many priceless books and manuscripts, the Book of Kells is far and away the most significant. Considered to be the finest illuminated work in existence, the 680 page collection was produced by monks living in Kells, Northern Ireland, during the early 2nd century. These religious artists devoted their lives to copying and painting the gospels of the New Testament.

The Long Room at Trinity College. Photos from Wikipedia.

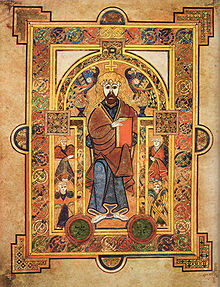

Intricately illustrated manuscripts within the Book of Kells.

The patterns and ornamentation of the Kells are blindingly intricate and complex. Figures of all kinds have been illustrated: human, animal, and imaginary beings. Celtic knots, with interlacing color patterns — some consisting of 158 distinct ribbons — frame the pages. It’s impossible to look at the illustrations and not be touched by the amount of labor that was required to produce each individual page. Also interesting are the unusual ingredients used to create the paints: shellfish, beetles wings, and crushed pearls. But the bizarre combinations produced color pigments that are still vibrant and fresh-looking 19 centuries later.

Other illustrated manuscripts on display in the library include the Book of Armagh, a 9th century copy of the New Testament and the Book of Durrow, a 7th century book portraying the gospels. Also worth seeing is the medieval Gaelic harp, called Brian Boru. One of three surviving ancient Irish harps, this particular instrument is also the national symbol of Ireland and appears on the Irish Euro coins.

DEAR SAINT PADDY

As I exit the library, the rain has stopped, although heavy, steel wool clouds hang thick and ominous overhead. I decide to take a quick fish & chips break and then walk over to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Dublin, by the way, is a very compact, pedestrian-friendly city — no problem getting around.

St. Patrick’s is the largest cathedral in Dublin. Legend has it that the church marks the site of an old well where St. Patrick baptized hundreds of converts. The main structure, is classic English Gothic, built in 1254. The Lady Chapel was added in 1270.

When Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church to marry Anne Boleyn, St. Patrick’s, like all churches under English rule, was made into an Anglican Church. In 1937, when Ireland won its independence from Britain, many Catholic churches reopened or converted back to Catholicism. St. Patrick’s, however, remained Anglican.

The carved images of St. Patrick and Jonathan Swift at Dublin Castle. Photos by Marla Norman.

The most famous Dean of St. Patrick was Jonathan Swift, whose tomb is in the cathedral. Swift is best known now for his novel Gulliver’s Travel’s. But during his lifetime, his essay A Modest Proposal, suggesting that Irish children could be exported as food to England, outraged British readers. Swift’s bitter satire on Anglo-Irish relations helped draw attention to harsh British rule in the 1700’s.

Just as I finish touring, the rain stops. I take a seat in the beautifully landscaped garden and — I’m not making this up — right on cue, a perfect rainbow appears over the cathedral. I’m thrilled by both the sun and gorgeous colors. What I don’t realize until later is that rainbows are quite common in Ireland. It’s locating a dry spot to observe them that’s the tricky part.

RULERS & REBELS

Next up is Dublin Castle, the site of British rule in Ireland for more than seven centuries. In fact, the original structure was built by King John in 1220. In addition to administrative functions, the castle served as a prison for numerous Irish leaders supporting independence. The castle was also the strategical center for the British effort during the Anglo-Irish War.

Woven carpets and Waterford crystal chandeliers at Dublin Castle. Photo by Marla Norman.

Now, since Ireland’s independence, the castle is used primarily for Irish State functions. I visit the impressive Wedgwood Room, which includes elegant Donegal rugs and a pretty marble fireplace. Even more splendid is St. Patrick’s Hall, with heavy woven carpets and multiple Waterford crystal chandeliers. It’s here that visiting heads of state and EU ministers are entertained.

On the castle’s exterior walls, are more than 100 carved heads. St. Patrick is one of the most prominent. Jonathan Swift, St. Peter, and Brian Boru are also among the collection. From the somber, stately castle, I move on to rowdy, lively Temple Bar.

REVELERS, CHORISTERS & SCRIBES

Sir William Temple, provost of Trinity College in 1609, lived in what is now Temple Bar, and supposedly lent his name to the neighborhood. The area is the location of many important Irish financial institutions, particularly the Irish Stock Exchange and the Central Bank of Ireland. Cultural organizations such as the Irish Film Institute and National Photographic Archives are there as well.

The Temple Bar district is known for its restaurants and over-the-top nightlife. Photo by Marla Norman.

But Temple Bar is known mostly for its over-the-top nightlife. Numerous restaurants and bars cater to tourists and festive locals. The music and merrymaking is contagious. As I make my way through the crowds, I bump into a group of Elvis Lookalikes who, in typical Irish fashion, immediately introduce themselves and explain — in captivating detail — that the costumes are for a surprise birthday party.

Irish Elvises – off to a surprise birthday party. Photo by Marla Norman.

After chatting with the Elivses, I continue on, stopping to listen to fiddles in one bar and jigs in another. Street musicians are on every corner entertaining large groups of people. Several hours fly by before I realize it’s well past midnight.

On my last evening in Dublin, my head is filled with local stories, more than a few great Irish histories, and of course, “a wee bit o’pint.” It’s a little dizzying. I’ve experienced first hand the “incurable disease” aka the Irish penchant for storytelling. Hopefully this is one illness that will remain, forever, untreatable.