Vietnam: Sapa Town

by Scott McIntire, travel blogger for GLOBOsapiens

After completing my tour of the Bac Ha Sunday market and a traditional Flower H’mong house at the nearby Ban Pho village, we begin the 110 km drive to the town of Sapa. We retrace our earlier route back to Lao Cai, save for a stop outside of Bac Ha at a roadside fruit stand where my guide buys some papayas to take home to his family. Once back in Lao Cai, we cross the Red River and continue southwest along (national road) QL 4D towards Sapa, enjoying the scenic views that unfold during our winding ascent.

We arrive in Sapa about 2:00 p.m., passing by the town’s picturesque lake and the public square in front of Sapa Church en route to my hotel. We turn left onto P Cau May Street, which is the primary destination for arriving tourists given its concentration of restaurants, cafes, tour agencies, and western-geared hotels and guest houses. It becomes readily apparent that P Cau May is also the primary destination for the town’s numerous wandering Black H’mong and Red D’zao hill tribe vendor girls and women eager to sell traditional tribal handicrafts and trinkets to the arriving tourists. The driver stops to let my guide and me out in front of the Chau Long Sapa Hotel, which is located near the south end of P Cau May Street.

I’m a bit surprised to learn after checking into the hotel that I have to surrender my passport to the hotel for a period of about 6-8 hours. My guide explains that my passport would be reviewed by the provincial party officials, who need to know the particulars of any foreigner entering the region. As the hotel is built on a mountainside, its split-level design puts my fourth floor room one floor below the street level entrance. The room affords a good view of the valley and the surrounding mountain peaks when the weather permits; given its location and 1650 meter elevation, Sapa sees a lot of fog and rain, and visibility can change quickly with the shifting winds.

I leave my small pack in the room and walk back up to P Cau May Street to begin exploring the town on foot, and soon have my first of many encounters with the wandering hill tribe vendor girls. The local Black H’mong and Red D’zao girls, wearing traditional costumes and toting their tribal handicrafts and garments in embroidered sling bags or draped over their arms, are an ever-present sight in town; their persistence in trying to make a sale can eventually try one’s patience, if not become down-right annoying. A visitor browsing at the offerings of one vendor girl may soon attract several more, and one seated at a sidewalk cafe or restaurant may be seen as a captive potential customer.

The Black H’mong hill tribe vendor women, who are in the majority of those encountered, wear indigo-dyed and multicolor embroidered hemp or cotton cloth jackets, aprons, skirts, leggings and pillbox hats. The vendor women of the Red D’zao hill tribe wear indigo-dyed and white or multicolor embroidered jacket and pants, and large red turbans which make them easy to distinguish; per their tradition, the women shave their eyebrows and their hairlines back to high on the forehead to denote wisdom. The Black H’mong vendors, which tend to be younger than the Red D’zao, are perhaps the most friendly and business-savvy of the ethnic minorities encountered on the streets of Sapa. They also tend to exhibit the best command of the English language among the local hill tribes, and can be quite open with regard to what they reveal about themselves and in the personal nature of the questions that they may ask in conversation. Some members of the Flower H’mong and Giay hill tribes are also in town.

I continue my uphill stroll in the direction of the public square and familiarize myself with the nearby restaurants, cafes and businesses. Given Sapa’s mountainside layout, some of the fairly steep streets that intersect with or run parallel to the inclined P Cau May are accessed via quaint stair-stepped cobblestone walkways. As I continue one, a Red D’zao vendor woman toting an umbrella approaches me and offers to sell me something from her stock of handicrafts contained in a plastic shopping bag. Smiling, I politely refuse her offer and walk on. Undaunted by my lack of interest, she begins following me, staying about a half-step behind and periodically looking up at me with imploring eyes as she hold out another handicraft for my examination.

I take the steps leading down to the Sapa Market, which is located at the intersection of P Cau May and D Tue Tinh streets. The market’s open store fronts and tarpaulin-covered stalls sell the normal assortment of dry goods, produce, meats and fish, and household items. Most intriguing are the bottles of medicinal rice whiskey that contain ginseng roots and a coiled cobra with a scorpion held in its mouth by the tail. The market’s hill tribe handicraft vendors are mainly concentrated upstairs inside a building fronting P Cau May.

I work my way through the market taking photos, with my new-found Red D’zao friend and her bag of handicrafts close by. She gives me quizzical looks as I contort and position myself to frame different compositions, and at one point asks why I would even bother taking pictures of a parked motor scooter. Back up on P Cau May, as she holds up a small decorative wall hanging of red and black cloth embellished with embroidery and silver jewelry, my will is finally broken; I purchase the piece and, after taking a photo of her, we at last part company.

I walk to the nearby public square where a number of hill tribe vendors sell their traditional handicrafts laid out in the open atop blankets on the pavement. Much of the black and dark blue hill tribe fabric and clothing offered for sale is dyed with local indigo that is not set into the fabric. Blue-green stains, visible on the hands and clothing of the vendors, provide ample evidence of that fact. There are also a number of Vietnamese vendors in the square with their goods for sale displayed beneath tarpaulin canopies that line the periphery of the square.

After an early-evening plate of beef fried rice and a large Lao Cai Beer (67,000 Vietnamese Dong; USD $3.22) for dinner, I swing by the hotel to retrieve my passport before continuing to explore the town on foot. While heading back towards the public square, I’m stopped by a Black H’mong vendor girl wearing her traditional indigo jacket over a printed T-shirt. She’s intent on selling me something from one of the tribal sling bags hanging from her shoulder. I patiently express my lack of interest in buying anything and turn to continue on my way, but a simple three-word entreaty conveyed in a particularly lilting feminine voice causes me to pause and look back. “Buy from me…?” Her attire is the first thing that sets her apart from the other myriad vendor girls encountered since arriving in town, and to me the styling looks distinctly Chinese. Her pastel plum blouse, white pleated skirt and belted sash are all ornately embellished with embroidery, sequins, imitation gemstones, lace and beaded fringe tipped with small dangling silver charms.

With a playful grin and a mischievous gleam in her laughing eyes she continues her routine — undoubtedly well-honed and practiced — all calculated to charm a prospective customer. “You buy from me? Buy-from-me-buy-from-me-buy-from-me…?” She gazes up hopefully into my eyes while maintaining her playful grin. When I smile and say that I’m really not looking to buy anything, she over-dramatically conveys feigned disappointment by letting her grin slip into a somber frown as she tilts and lowers her head while pursing her lips into an exaggerated pout beneath her now downcast eyes. “If you don’t buy from me, I’m gonna…DIE!” The last word is said in a deep voice and drawn out long enough to comically emphasize the mock gravity of the situation. When my laughter subsides, I ask her name and enquire about her ethnic minority heritage. I learn that her name is Ha, and that she is a 17-year old Black H’mong from a nearby village called Cat Cat. She says that she wears a costume in the style of the Chinese H’mongs because it makes her stand out, which is very good for business; she then quickly gets back down to business. “Blah-blah-blah-blah-blah; all you do is talk! Are you going to buy from me? ” My will yet again broken, in part by her quirky yet endearing personality; I opt for a small Black H’mong mouth harp called a ‘jew’; it is made from a brass leaf and cased in a bamboo tube covered in embroidered fabric, and apparently used in H’mong courtship. She quotes it at 60,000 Vietnamese Dong, and then drops it to 50,000 Dong. I end up getting the harp for 30,000 Dong, and take a few pictures of Ha and her friend, whom approached me first and has stayed nearby during our transaction, before going on my way.

I ascend the stair-stepped walkway to a quiet street that runs parallel to P Cau May and leads up to the Sapa Church. I hear the faint sound of what seems to be live traditional Vietnamese music being played up ahead and go to check it out. Following a bend in the narrow road, I end up at the side entrance of a small hall adjacent to the Sapa Church with a number of people standing around and conversing out front. Walking into the hall, I see what appears to be seated members of an extended family dressed in white robes surrounded by others in respectful attire; surmising that the live traditional orchestra is performing as part of a funeral service, I leave as inconspicuously as I can manage.

I walk along D Ham Rong Street, which flanks the church and the town’s lakeside park. Along the side of the road are a number of grilled-food vendor stalls housed in a long continuous row of adjoining tarpaulin canopies; a line of bare hanging light bulbs illuminates the haze of rising smoke as fat and marinade droplets sizzle on hot wood coals. As I stroll among the barbeque grills being fanned with woven cane mats, the enticing savory-sweet aroma make my mouth water even though I’ve already had dinner. I’m beckoned to take a seat by a litany of hellos from hostesses and waitresses standing behind platters of enticing grilled meats, whole fish, large prawns and assorted vegetables. I accept an extended invitation at one of the stalls and order a Tiger Beer. Though a couple of other foreign tourists are seen milling about, the assembled diners seated at the low tables in petite blue and red plastic chairs are all locals. Little English is spoken and my Vietnamese is limited to some basic words and phrases, but I still manage to communicate with those around me, with the sharing of my photos and video clips of the Bac Ha market helping to break the ice and bridge the cultural divide.

I take the stair steps back down to P Cau May and head back to my hotel. Sapa’s ‘tourist zone’ is pretty sedate on a Sunday night, with only a modest number of people out strolling the street and few vehicles going by. Somewhere nearby, perhaps just beyond the open accordion-style doors of one of the souvenir shops, a person is improvising somber-sounding melodies on a type of flute or reed wind instrument; the instrument’s melancholy wail merges with the sputtering growls of passing motor scooters, providing a soundtrack befitting the laid back mood of the street.

The morning is cloudy and gray, with drizzle and a thin fog beginning to drift up from the valley. I take a few photos from my room’s balcony before heading up to the breakfast buffet, and then out front to wait for my guide. The fog is settling in as my guide arrives and we walk up to meet the car. We drive about 8 km due northeast of Sapa, then exit the car and being hiking along a rock-strewn dirt road; it leads through a stretch of trees and tall brush to a ridge line that overlooks a valley veiled in a haze of thin fog. Even with the limited visibility, the numerous stair-stepped rice terraces on the nearby slopes are still a sight to behold. As the road follows its sinuous course down into the valley, more expansive views of the terraces are opening up before us.

Down in the paddies, the Black H’mong women, many wearing traditional black hemp jackets and Vietnamese style ‘non la’ conical straw hats, appear to be performing the bulk of the work. One of the women has a baby secured to her back with a wrapped blanket harness as she leans down to transplant a seedling in the paddy’s soft mud bottom. A young girl nearby uses the same technique to carry her baby sibling as she carefully walks along a muddy trail that runs between the terraced paddies; I later take a photo of her as she watches her mother from behind barbed wire fencing. Other children play nearby amid grazing water buffalo while their family members work in the paddies; their young voices and laughter mix with the sounds of water gurgling down the rungs of the terraces, the sloshing of ankles treading through brown water and the murmur of conversations from the paddies, the calls of birds and croaking frogs, and the dull hollow clanking of buffalo bells.

The colors of the paddies vary with the stages of the rice cultivation cycle; those with well-established maturing stalks or seedlings that are grown for transplantation appear as lush curving bands of forest or yellow green; the fallow or bare earth paddies convey the hillside contours in stripes of dull brown and reddish earth tones; paddies that have been flooded and are awaiting transplantation of seedlings present like stacked curved ribbons of dull white or light beige fringed in brown as the overcast skies above are reflected between the tops of the earthen levees; those that have been planted with the evenly-spaced seedlings appear light green or pastel gray-green in color. In addition to being visually stunning, the hillsides of rice terraces are all the more amazing given that they had been built by hand with the help of plows pulled by water buffalo.

Further down the trail we enter the Black H’mong village of Ma Tra, where my guide says we will spend some time touring a traditional village home; he adds that he has brought some small cakes to offer to the children of the family, and that I am welcome to also offer something to the family. We stop amid a small group of wood and corrugated tin roof houses, and enter one of them after my guide announces our presence. The rustic interior is illuminated by the natural light coming through two open doorways and a small window, and the open spaces that provide for ventilation between the walls and framing of the house and the corrugated roof; the gaps between the wall’s vertical wood planks also contributes to the illumination and ventilation. The rough concrete floor of the house features a fire pit encircled by flat rocks, with a section of steel rebar bent into an elongated ‘U’ supporting a soot-blackened kettle; an old treadle-operated sewing machine and a manual weaving loom sit in the corner of the main room of the house near one of the doors to take advantage of the natural light.

Two elderly Black H’mong women are present in the home, the eldest being the 92-year old matriarch of the family; the somewhat younger of the two is sitting by the fire pit and smoking locally-grown tobacco from an old black bamboo pipe. My guide takes a seat on a small wooden stool by her and introduces me to the women and the children of the extended family. The ten young children that are currently in the home at first congregate atop or in front of an old wooden pedestal bed, beneath which lay an assortment of rubber boots in various sizes, colors and amounts of residual mud; after some initial apprehension, their curiosity sets in and they start mingling with me. My guide next offers me a sample of the local tobacco from the younger auntie’s pipe. Sitting across the fire pit from auntie, I hold the pipe’s opening to my lips and inhale; the harshness of the smoke causes me to cough vigorously, which of course causes everyone else to laugh hardily. My guide distributes the sweets to the village kids, and then walks me around to point out the various features of the house. Perhaps the most interesting feature is the family meat storage area, where portions of an animal carcass are hung from the ceiling.

After the brief tour of the home, I thank the aunties for their hospitality and give them each a quantity of Vietnamese Dong as a gift to the family before we take our leave; some of the kids follow us outside and I take some photos and a video clip of them before we continue on. The trail gradual works its way uphill, passing other small groups of rustic houses and myriad rice terraces flanked by wooded hills veiled in drifting fog. We approach a terrace of transplanted seedlings that are being worked just off the trail. The nursery paddy at the top of the terrace is occupied by at least a dozen Black H’mong villagers in the process of uprooting seedlings and bundling them for transplantation. Below it are several flooded paddies with bundles of seedlings laid out for planting. My guide calls out to the villagers to get their attention, then tells me that we will go down to the terrace for a closer look, and that I can even try my hand at working in the paddy if I want to.

I step down onto the second rung of the terrace and take some video of the scenery and the activity in the paddies. I confirm with my guide that I can briefly try my hand at working a rice paddy; he tells me that I can either try uprooting the rice seedlings for transplantation from the nursery paddy, or try re-planting the seedling into a flooded paddy, and that I don’t have to worry about leaches in this part of Vietnam. As the nursery paddy has more villagers working in it, and it appears to be quite lively given the fair amount of chatter and laughter going on between the younger Black H’mongs, I opt for uprooting seedlings; my guide holds my cameras while I’m in the paddy, and tells me that he will also take some photos and videos to document the experience for me.

I carefully step into the ankle-deep, cappuccino-brown water and feel the warm, slimy mud slowly extrude up between my toes as my bare feet settle to the soft bottom of the paddy. Even though there is no benefit in doing so, I look down at the surface of the opaque water as I take my first tentative steps, which causes the large black water striders around my ankles to quickly dart away. At the sound of laughter, and at least one feminine squeal of delight, I glance up to see the smiling and bemused faces of the villagers who have been pulling up seedling stalks at the far end of the paddy; I manage to make it across to them without doing a face-plant into the muddy water. My mentor, a smiling and patient Black H’mong woman, shows me the proper uprooting technique (right hand palm-up, thumb and index finger at the base of the stalk pressed slightly into the mud, light squeeze, s-l-o-w-l-y pull up), then bundles my seedlings and ties them together with a long grass-like rice leaf.

As I uproot my first seedlings, a bit of paddy field horse play between a Black H’mong girl and two boys that seem to be in their late teens or early twenties escalates into a friendly mud and water fight; the confrontation must have been a long time in coming, as the girl and one of the boys was already streaked with mud when we first approached the paddy. At one point, the girl gets between me and my mentor, and her mud-slinging leaves me with some brown speckles on my shirt; I’m hoping that my guide captures some of the fray on video. After my brief stint in the paddy, I follow the lead of a Black H’mong girl and wash my feet and legs in a small stream that sources some terraces below; after shooting some photos and video clips, we are again on our way up the trail to the Red D’zao hill tribe village of Ta Phin. In reviewing the photos and footage that my guide has taken, I see that he has not only captured images and video of me in the paddy and the ensuing mud and water fight, but also an image of a Black H’mong girl that’s captured his fancy.

Continuing to gain altitude as we proceed along the trail, we are treated to farther reaching views of the colorful rice terraces when the weather cooperates; we encounter more villagers along the trail, and my guide often stops and chats with them while I’m off framing photos and slow-panning video clips. I notice that the battery life on my small digital camera that is dedicated to shooting video (the still photo capability having earlier ‘gone south’ back in Singapore) is a bit less than half, so I decide to save the power for my planned self-guided trek to the nearby Black H’mong village of Cat Cat after we have lunch and return to Sapa. Along the crests of the hills, the slopes just above the tops of the terraces are cultivated with rows of corn and indigo and dotted with hemp plants; these crops can thrive solely on the precipitation and thus don’t require terracing and irrigation. We begin seeing pine trees along our path, which is something that most do not normally associate with Vietnam or Southeast Asia.

At this point in the trek, we leave the dirt road and occasional passing motorcycles behind and divert onto a narrow dirt trail that meanders up a hillside; the land is lush with crop fields, ferns and scattered pine trees, and the prominent rocky outcroppings backed by mist-veiled mountain ridge lines adds to the picturesque quality of the surroundings. We hike along a stretch of grassy clearing that’s flanked by pine trees and striped with a narrow red dirt track down the center that was likely a road during the French occupation.

We stop at the atmospheric ruins of an old French monastery just outside of the village of Ta Phin. We are running behind schedule, and by the time we enter the village it is quiet, with the resident Red D’zao villagers resting after their morning’s work out in the field. My guide suggests that we head back to Sapa rather than intrude upon the villagers. We locate our driver and get on the road.

Take a virtual trek amid rice terraces and hill tribe villages on the outskirts of Sapa.

My guide and I are dropped off in front of a restaurant at the corner of P Cau May and D Dong Loi, just up the street from my hotel. We step inside and take a booth, after which my guide produces a plastic grocery bag from his nap sack and places it on the table. As he removes the contents of the bag (a fresh baguette, a pull-top can of tuna, some sliced tomatoes and cucumbers), he tells me that we were supposed to have a picnic lunch out on the trail, but because of weather and timing, the plan had changed, and that the restaurant would allow me to eat my outside lunch seated in the booth. He adds that this is the end of the day’s scheduled activities until 5:00 p.m., when I would be picked up at the hotel and driven back to Lao Cai to board the night train back to Hanoi. I shake his hand and thank him for the morning’s guided trek.

As I eat, I consider my available time before leaving Sapa and devise a viable schedule; I figure that if I can limit a roundtrip trek to Cat Cat to about two and a half hours, I will have some time to relax and see a bit more of the town before meeting up with my guide and driver. I finish my meal and turn to leave, only to see a lot of people crowded along the sidewalk and curb out front and hear the sound of beating drums and crashing cymbals coming from up the street. It is apparently the funeral procession associated with the gathering that was being held last night next to the Sapa Church.

The procession is lead by men and women carrying large flags and colorful banners with the image of the Buddha on long staffs; they are followed by a van from which someone is tossing out some type of small packets from the window to the crowd at periodic intervals. Next are women in black pants and long black gowns wearing peaked non la conical hats (some are also wearing loops of Buddhist prayer beads around their necks) carrying multicolor banners on staffs, with many of them forming a line and holding a long bolt of yellow cloth with black borders at shoulder level like a dragon in a Chinese New Year parade; the far end of the cloth is attached to a wheeled shrine cart, and some of the women holding the cloth also toss out flyers with big concentric red and yellow rectangles printed on them. Two men carry a large red drum suspended from a yoke carried across their shoulders as another man strikes a gong that he carries; men in naval-looking uniforms and caps play a small drum and traditional ken bau wind instruments that can’t be heard over the din of the large drum and cymbal strikes. Finally, the ornately-decorated funeral cart bearing the deceased passes, pushed by uniformed pall bearers and those close to the deceased, followed by the somber family members in white hooded robes, with others in the crowd of followers wearing white headbands. The procession pauses briefly near the end of P Cau May before moving on, at which time I begin my trek to Cat Cat village.

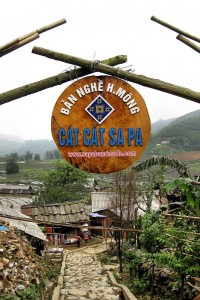

I take the steps that lead down from P Cau May through the Sapa market and onto D Tue Tinh Street, and then continue downhill onto D Phan Si Street, which quickly takes on the feeling of a country road. As I walk, the breaks in the trees along the left side of the road reveal views of rice terraces and crop fields in the fog-shrouded valley below. I shortly come to the ‘Cat Cat Tourism Area’ ticket station, where a 30,000 Dong village admission fee is paid, and a ticket is given that must be later presented at the ticket checking station at the entrance to the village. I continue on the often-steep and winding 1.3 km decent into the valley along well-worn tarmac towards the village, passing rural homes, a couple of roadside vendor stalls, and Black H’mong villagers both on foot and on motorcycles along the way.

Given the 2-1/2 hours of trekking this morning and the fatigue that I’m already beginning to feel even on the early downhill portion of this hike, I figure that I’ll be pretty tired by the time I make it back up to the hotel. As I’m thinking this, I hear the sputtering purr and rattle of an approaching motorcycle slowing to a stop next to me. It is one of the ‘xe om’ motorcycle taxis that cruises the route to Cat Cat village in hopes that tourists may suddenly find themselves too tired to walk any further and wish to make use of their services. His says that his name is Star, and proudly points to his namesake painted on his helmet. He asks if I’m heading to Cat Cat, then offers to drive me there and then take me back to Sapa, quoting “…whatever you think it’s worth” as the going rate. I pass on the offer, figuring that trekking was one of the reasons I decided to make the trip from Hanoi, and continue on.

I stop at the ticket checking station on the left side of the road to verify payment of the admission fee, then proceeds downhill to the village along the flagstone-paved stairs and walkways. The village is quite scenic, with picturesque rice terraces flanked by steep wooded slopes, but it feels too touristy when compared to the morning’s visit to the village of Ma Tra. The village may have started out as traditional, but it had since been developed with tourists in mind, with a museum house, souvenir stalls and a cultural performance venue. I follow the stairway down to the photogenic Tien Sa waterfall and sounds of traditional Vietnamese music playing on overhead loud speakers, which is pleasant enough but adds to the subtle ‘theme park’ vibe of the village. A visit to Cat Cat village would definitely be a viable option for the visitor who has only limited time in Sapa, but still wants to do some trekking and sample a bit of the Black H’mong culture. I glance at my watch and decide that I will have to pass on Cat Cat’s other attractions further down the trail, and high-tail it back to the hotel. However, given the altitude and number of steps leading back up to the village from the waterfall, I’m soon out of breath and realize that high-tailing is easier said than done. A passing cool breeze and a light sprinkle of rain helps to reinvigorate me for the trek back into town.

Experience the environs of Sapa and the Black H’mong hill tribe village of Cat Cat.

Sore and exhausted, I’m back on the south end of P Cau May with some time to spare; I had already checked out of the hotel before the trek to Cat Cat and just need to retrieve my pack from the front desk, when my guide and driver show up. I stop at a nearby convenience store and pick up a few small packs of cookies for the train ride back to Hanoi. It’s nearly 5:00 p.m., so I return to the hotel; on the way, I smile when I see Ha’s familiar Chinese-styled pastel plum blouse and white pleated skirt ensemble up ahead, and walk over to say hi. She jokes that I paid too little for the H’mong mouth harp, as it was supposed to be 60,000 Dong instead of the 30,000 that I paid, and that the way she sees it, I still owe her something. I reach in my knap sack and hand her one of the packs of cookies that I’ve just bought. She takes it, and with a little smile reaches into her ethnic sling bag and produces two cloth tie-on bracelets embroidered with traditional H’mong design elements; she hands them to me, saying that they are a gift. I wish her good luck and good bye, and then walk over to the hotel where my guide and driver are now waiting.

The late afternoon sky is hazy and overcast as we drive back to Lao Cai. As the road winds up the mountain slopes, we can see some terraces across the valley that have been harvested and appear to be having the remains of their dry rice stalks burned off; as the muted daylight further wanes beneath a drifting bank of gray moisture-laden clouds, the distant flaming paddies look like sinuous stripes of yellow-orange neon lighting. We pull into Lao Cai with time to spare before the night train departs for Hanoi. My guide is thirsty, so we stop at a city park that features a few sidewalk vendors and grab some freshly-wrung sugar cane juice. From there, we walk a few blocks over and stroll among the street produce and food vendors; due to the city’s location on the border, much of the signage is in Chinese characters.

As we walk, my guide tells me that before going to the train station, we will first spend some time at a ‘bia hoi’ (a type of beer pub/restaurant) located nearby called Bia Hoi Lao Cai; he mentions that he likes to bring all of his tourist clients to that particular place to let them authentically experience Lao Cai the way the locals do before they leave northwestern Vietnam. ‘Bia hoi’ (‘drop beer’ in the local slang) is basically a no-preservatives draft microbrew beer that is meant to be consumed immediately after it completes the brewing process; the term bia hoi is also used to refer to an establishment that sells the microbrew together with snacks that pair especially well with it. He tells me that Vietnamese men generally get off work at 5:00 p.m. and head directly to a bia hoi and stay until about 7 PM, at which time the go home to their wives and families. There is seating both inside and outside, though most people seem to prefer sitting outside on cheap blue plastic chairs placed around folding tables, which is what we opt for.

We order a plate of nem, one of the popular bia hoi snacks. Nem is a salt-cured fermented pork charcuterie made with garlic, chili and white pepper. Our order is partially overlaid with an aromatic spice leaf then wrapped in banana leaf for curing; afterwards, it’s taken out of the banana leaf and, with the overlaid spice leaf still attached, dipped in either fermented shrimp paste or a vinegar-chili dip sauce and eaten. We also order cubes of fried tofu, which are wrapped in a small basil-like leaf and dipped in a red chili paste. Both snacks are quite spicy and well-complimented by the bia hoi, which also helps to suppress the chili after burn. Unfortunately, two days later back in Singapore I would have three days of ‘tummy trouble’, which could have been due to the bia hoi snacks or the fresh sugar cane juice.

As we sit relaxing in our cheap plastic chairs and watch the evening approach while enjoying our spicy snacks and local brew, similarly-seated Vietnamese business men and laborers alike enjoy their brief respite from the demands of daily life; busy waitresses make their rounds of the tables, taking orders and carrying away empty pitchers; countless motorcycles whine past our bia hoi, leaving the scent of exhaust in their wake; women sit behind card tables on the sidewalk selling lotto tickets to hopeful passers-by and cars that briefly pull to the curb, only to quickly fold-up shop because the activities of these transitory vendors is said to be officially frowned upon. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say that I’m having the desired ‘Lao Cai local’ experience.

On the train ride back to Hanoi, I settle into my four-person sleeper. One of my cabin mates is actually a retired attorney from a city fairly close to where I live, who had closed his practiced and moved to Bangkok; he said that he was sightseeing in southern Laos but decided to head to Sapa to escape the high heat that much of South and Southeast Asia was presently experiencing.

With the quick jolt of the slack being taken out of the coupling, the train slowly begins its eastward journey, and I’m thinking that I’m just tired enough to maybe get some decent sleep, and that I’m also glad that I decided on adding the two-day Sapa excursion to my far too brief Vietnam itinerary.

Scott McIntire is an engineer who has worked in the aerospace and automotive industries, but whose true passion is traveling. He enjoys sharing his experiences on the road and abroad through his photos, videos and travel writing, and contributes to the travel blog GLOBOsapiens.