French Barrel Making: Tonnellerie Sylvain

by Marla Norman

Barrel making is an essential part of wine and an incredibly time-comsuming process. Photo by Marla Norman

So much of winemaking is a time-consuming process, from the planting to the cultivation to the harvesting, fermenting and aging. An equally laborious and essential task, is barrel making. Over three years is required for the construction of a barrel. And if you calculate the length of time for an oak tree to grow – hundreds of years are involved.

France is the world leader in barrel making, producing more than 500,000 casks annually, for a market value of well over $400 million. There are 100 coopers – barrel makers – in France. One of the top manufacturers is Tonnellerie Sylvain in Libourne, Bordeaux. Rodrigo Luna, the company Export Manager, accompanies me as we walk through row after row of 6-foot tall, neatly-piled stacks of wood on the Sylvain property.

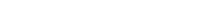

Rodrigo Luna, Export Manager for Tonnellerie Sylvain checks a plank in one of hundreds of stacks on the company property. Photo by Marla Norman.

Most of the wood used for barrels comes from central France. These are the forest lands planted by Louis XIV, who wanted high-quality hardwood to build ships for the French navy. To this day, the best oak comes from this area. “This is an early example of forestry management,” explains Rodrigo.

The French government owns 40% of all forested land, including the original tracts planted by Louis XIV. Once a year, various areas are put on auction and companies, like Sylvain, bid on them. It’s a complicated, bureaucratic process. And very expensive. Half the cost of a barrel is in the purchase of timber – or around €400 for raw timber alone, since the cost of a finished barrel is €700-€1,000.

“Consistency is the most important thing,” Rodrigo continues. “So we try to always buy similar oak from similar plots. We don’t want to experiment with other woods or sources.”

Quercus Petraea and Quercus Robur are the two types of oak used. “Quercus Petraea grows more slowly than Robur and it’s more aromatic and less tannic than Robur. The fine grain in these oaks is a result of the quality management of the ONF (French National Forest Office) who oversees high density tree growth,” adds Rodrigo.

“Every year, Sylvain offers collection barrels made from remarkable old trees,” continues Rodrigo. “Some of them are Morat, Colbert, or Aberdeen trees. We can only buy a tree of this age and quality if the ONF decides to sell it. The tress are the witnesses of the forest history. We want to keep them as long as we can, but sometimes they suffer xylophagous insect attacks and can die. Before that happens the ONF prefers to offer a second life to those trees by selling them. Dead trees can’t be used as raw material.”

Once the trees are cut they’re transported to Sylvain, where they sit eight months before they are split. The huge timbers are constantly sprinkled with water to protect them from the sun and xylophagus insect attacks. Later, the wood is inspected and precisely marked to be cut. Bark, soft wood and portions with excessive sap are discarded. In the end, only 20% of the tree is used.

After the timbers are cut into planks, they are stacked outside again, this time to season for two years. “Nothing can replace natural seasoning to reduce tannins, but it does take considerable time. The sun and rain are both important for fungus and enzyme reactions,” says Rodrigo.

Sylvain coopers expertly bend the planks within the iron stays used to assemble the barrel. Photos by Marla Norman.

After curing for two years, the planks are baked in a massive oven. With this process, the hygrometry or measurement of moisture content of gases and humidity is controled. Next, the planks are trimmed with a slight curve and bevel to create staves. Now the wood is ready for the cooper.

As we enter the main building where barrels are assembled and toasted, the aroma is deliciously pungent and fragrant. We watch one of the Sylvain coopers expertly bend the staves within the iron stays used to assemble the barrels. He works quickly and makes it look easy. It’s not!

Braziers with burning wood chips are used to smoke and toast the inside of the barrel. A light toast is for white wines and to add a bit of freshness. A heavy toast for full-bodied wines and to add caramel flavors.

A light toast is frequently used for white wines, while a heavy toast is used for full-bodied wines. Photos by Marla Norman.

The top of the barrel is glued on with a flour paste. Once dry, the barrel is filled with water to test. If there is a leak, the barrel is completely taken apart and reassembled or discarded all together. In the final stages, the barrels are air dried to kill fungus and then polished. The iron hoops, used during the original assemblage and smoking, are replaced with dress hoops. A head hoop is applied to decorate the barrel and provide a handle.

The last step is branding the barrel with the name of the maker, in this case Tonnellerie Sylvain, and the name of the client. “Who are some of your customers?” I ask Rodrigo. He rattles off a stellar list of world renown winemakers. “Here in France we work with Château Latour, Château Mouton Rothschild, Château Cheval Blanc to name a few. In the U.S. we have Screaming Eagle, Harlan, Mondavi and J. Lohr.”

“We produce between 120-130 barrels a day for about 31,000 barrels a year. So, we need about 2 months to process orders.”

“And a few years for the trees to grow.”

“That’s the most important part,” Rodrigo agrees. “It all starts with the trees.”